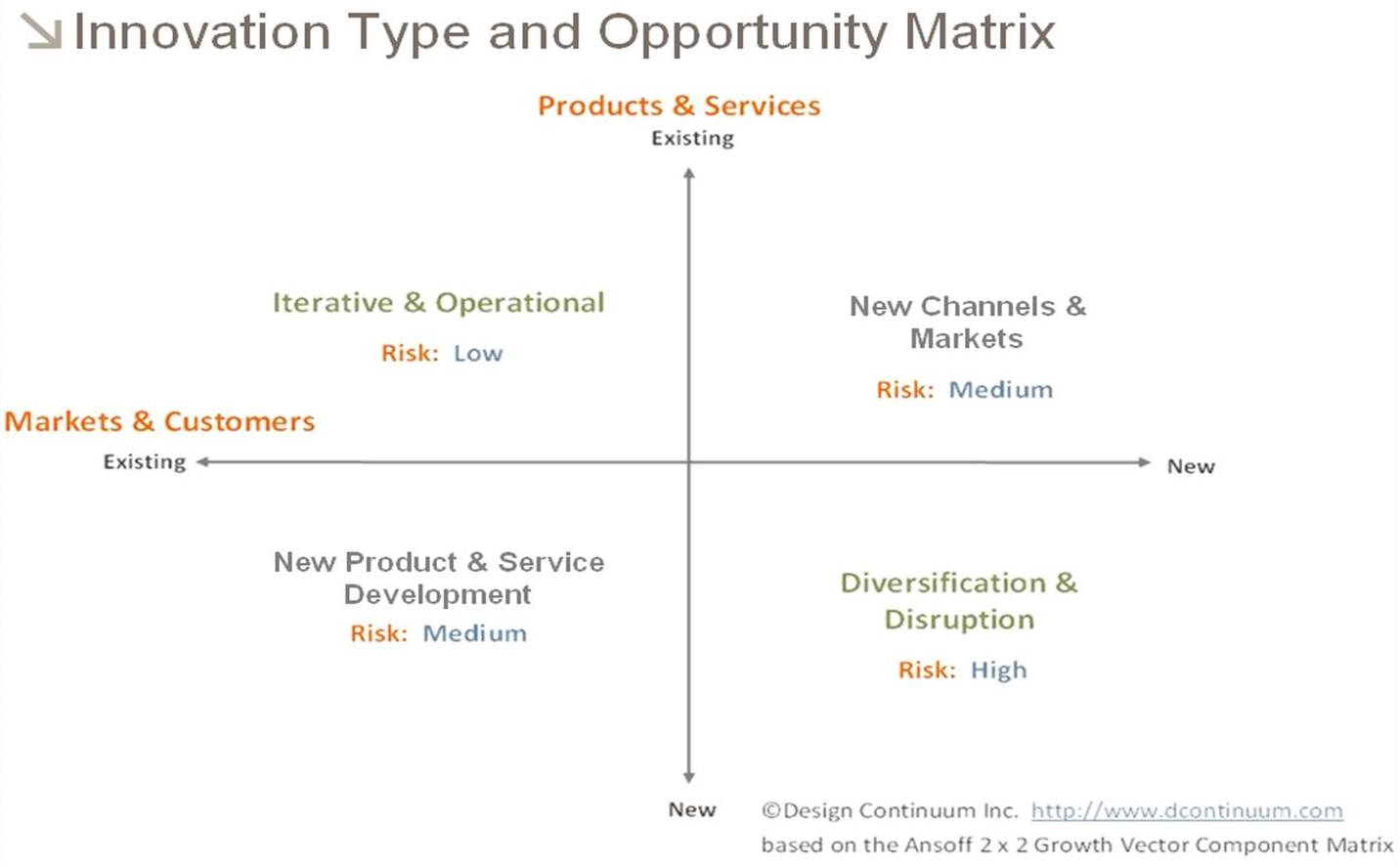

We’re all familiar with the Ansoff Matrix, from Igor Ansoff, „The Father of Corporate Strategy.“ This broadly-used model for corporate strategy planning has been subtly iterated since its first publication back in 1957, as pace-of-change- and level-of-sophistication of business have increased. Now it’s most-commonly used in the below form, to help companies understand their existing portfolios, help plan where they can realistically extend and help think about how to build completely-new areas of business.

Most Firms now have a portfolio of R&D and Innovation investments, placed across these quadrants, with the grouping depending on their growth planning and tolerance for the various risks in each quadrant.

It’s probably fair to say that every company aspires for a big win in the “New Markets & Customers / New Products & Services” quadrant, but investment there is most-risky and outcomes can be most disruptive to company cultures, existing markets and existing business models.

For most companies, the main barriers to success in the “new / new” quadrant are modeling outcomes, building intermediate project metrics and justifying investments. Projects in this quadrant are the most-likely to be stopped, because the initial business models that have been developed often appear much-weaker than those of competing project investments in other quadrants of activity.

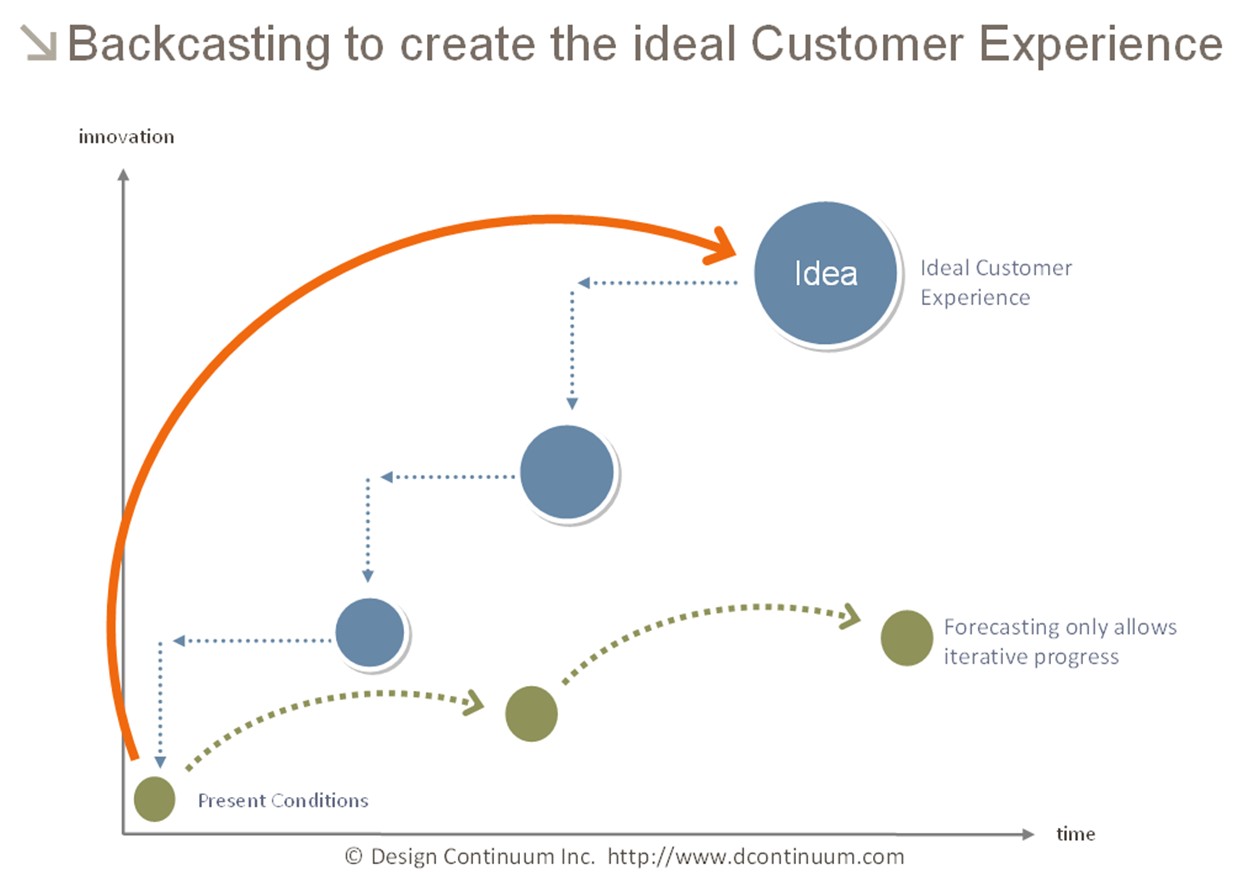

Usually, it’s the high risk in investing in the first few steps that kills a disruptive innovation project in its infancy—costs seem out of scale to the opportunity, level of resource commitment is usually very high, there can be disruptions to present business and time-to-profitability is uncertain.

The question that has often been posed is how companies can “let something grow a little longer,” before making a decision about its fate. Every company wants the growth that disruptive innovation brings, but they lack the tools to plan for it and measure its progress.

The Backcasting model is very powerful for planning investment in disruptive innovation. Using this tool, companies can envision a desired future, then plan backward to the present, making reasonable assumptions about evolving capabilities, resources and business conditions. Articulation of credible project stages and goals allows more-informed decisions about project trajectory, at each stage of its implementation.

This method differs from forecasting, since forecasting depends on assumptions of reasonable growth from existing conditions, based on historical performance and some “feel” from the forecaster. Forecasting can only ever be iterative, while Backcasting is used to build a roadmap, with checkpoints and metrics, to a completely-new future state.